Getting started with C programming on Linux

Share on:Edit on:Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Setting up the system

- Compiling and executing Hello World! program

- Behind the scenes of compilation

- Behind the scenes of execution

- References

Introduction

A programmer’s job typically involves writing a program, compiling, executing and debugging. This article helps any newbie to get started C programming language, including setting up the system for programming, the compilation process and execution mechanism.

Setting up the system

Learning C programming language on Linux based system is recommended. I use Ubuntu Linux Desktop for programming. Setting up the system typically involves installing editor, compiler and other programming tools if you have Ubuntu OS already installed. Otherwise install the Ubuntu OS.

Install editor, compiler and other tools

Enter the following command in the terminal to install tools.

sudo apt update && sudo apt install vim build-essential

Vim is a terminal based editor. build-essential package consists of gcc, g++, make utility and Gnu C library.

Compiling and executing Hello World! program

Run the following command in the terminal to open the file helloWorld.c with vim editor.

vim helloWorld.c

Write the following program in that file and save it.

/* Header file inclusion */

#include <stdio.h>

/* Main function */

int main(void)

{

printf("Hello World!\n");

return 0;

}

Compile the program by running the following command

gcc helloWorld.c -o helloWorld

Above command generates a binary called helloWorld. Execute the binary by running the following command.

./helloWorld

This should print the Hello World! output.

Hello World!

Behind the scenes of compilation

The process of compilation involves the following steps.

- Preprocessing

- Generating assembly code (Called compilation proper)

- Assembly

- Linking

Preprocessing

A preprocessing step by compiler includes macro substitution, inclusion of other source files, removal of comments and conditional compilation.

Consider the following program,

File : hello_new_world.c

#include <stdio.h>

#define HELLO_NEW_WORLD "Hello New World!"

/* Program starts from here */

int main(void)

{

#ifdef HELLO_NEW_WORLD

puts(HELLO_NEW_WORLD);

#else

puts("Hello World!");

#endif

return 0;

}

Run the preprocessor on the above file and save the output in a separate file. We can use the following command.

gcc -E hello_new_world.c -o hello_new_world.i

The output file hello_new_world.i has #include <stdio.h> replaced with the stdio.h file content; removed comments; removed some lines of code from the main function based on conditional compilation (if HELLO_NEW_WORLD is defined first puts will be processed or the other one) and substituted the macro HELLO_NEW_WORLD macro with its value "Hello New World!" (please check the last lines of following file).

File : hello_new_world.i

# 1 "hello_new_world.c"

# 1 "<built-in>"

# 1 "<command-line>"

# 31 "<command-line>"

# 1 "/usr/include/stdc-predef.h" 1 3 4

# 32 "<command-line>" 2

# 1 "hello_new_world.c"

# 1 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 1 3 4

# 27 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/libc-header-start.h" 1 3 4

# 33 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/libc-header-start.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/features.h" 1 3 4

# 446 "/usr/include/features.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/sys/cdefs.h" 1 3 4

# 460 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/sys/cdefs.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/wordsize.h" 1 3 4

# 461 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/sys/cdefs.h" 2 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/long-double.h" 1 3 4

# 462 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/sys/cdefs.h" 2 3 4

# 447 "/usr/include/features.h" 2 3 4

# 470 "/usr/include/features.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/gnu/stubs.h" 1 3 4

# 10 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/gnu/stubs.h" 3 4

# 1 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/gnu/stubs-64.h" 1 3 4

# 11 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/gnu/stubs.h" 2 3 4

# 471 "/usr/include/features.h" 2 3 4

# 34 "/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/bits/libc-header-start.h" 2 3 4

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

extern void funlockfile (FILE *__stream) __attribute__ ((__nothrow__ , __leaf__));

# 858 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4

extern int __uflow (FILE *);

extern int __overflow (FILE *, int);

# 873 "/usr/include/stdio.h" 3 4

# 2 "hello_new_world.c" 2

# 5 "hello_new_world.c"

int main(void)

{

puts("Hello New World!");

return 0;

}

Generating assembly code

The C code in the above file hello_new_world.i can be converted into assembly by the follwing command.

gcc -S hello_new_world.i -o hello_new_world.s

The output file hello_new_world.s has the assembly code

.file "hello_new_world.c"

.text

.section .rodata

.LC0:

.string "Hello New World!"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

main:

.LFB0:

.cfi_startproc

endbr64

pushq %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_offset 16

.cfi_offset 6, -16

movq %rsp, %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa_register 6

leaq .LC0(%rip), %rdi

call puts@PLT

movl $0, %eax

popq %rbp

.cfi_def_cfa 7, 8

ret

.cfi_endproc

.LFE0:

.size main, .-main

.ident "GCC: (Ubuntu 9.2.1-9ubuntu2) 9.2.1 20191008"

.section .note.GNU-stack,"",@progbits

.section .note.gnu.property,"a"

.align 8

.long 1f - 0f

.long 4f - 1f

.long 5

0:

.string "GNU"

1:

.align 8

.long 0xc0000002

.long 3f - 2f

2:

.long 0x3

3:

.align 8

4:

Assembly

This part converts the assembly file into relocatable object file (which is in ELF format).

gcc -c hello_new_world.s -o hello_new_world.o

At this point, this object file consists of following sections.

- .text - Program code

- .data - Initialized global variables

- .bss - Uninitialized global variables (Block storage start)

- .rodata - Read only data such as format strings, string constants

- Other custom fields.

Run the following command to see above sections.

objdump -h hello_new_world.o

The .text, .bss and .rodata contain functions, global variables and format stirngs mapped to addresses starting with 0. These addresses can be relocable when linked with other relocatable objects to form final binary executable. The linking step is explained below clearly.

Linking

The Linker’s job can be explained clearly with multiple source files.

Let’s assume the files a.c and b.c.

File: a.c

extern void print_sqrt_random();

int main(void)

{

print_sqrt_random();

return 0;

}

File: b.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void print_sqrt_random(void)

{

int rand_num = rand();

double x = sqrt(rand_num);

printf("sqrt of %d: %f\n", rand_num, x);

}

We can generate object files directly for a.c and b.c using following commands

gcc -c a.c -o a.o

gcc -c b.c -o b.o

We will use a tool called nm to check whether the functions (symbols) are defined in .text section of object file or not.

$ nm a.o

U _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

0000000000000000 T main

U print_sqrt_random

T indicates that the corresponding function is defined in .text section. U represents that the symbol is undefined. Here print_sqrt_random is undefined because the definition is in b.o object file.

$ nm b.o

U _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

U printf

0000000000000000 T print_sqrt_random

U rand

U sqrt

Here print_sqrt_random is defined in the .text section of b.o object file. And printf, rand and sqrt symbols are undefined because the definitions are defined in the libc and math libraries.

The linker’s job is to link these object files with the libraries.

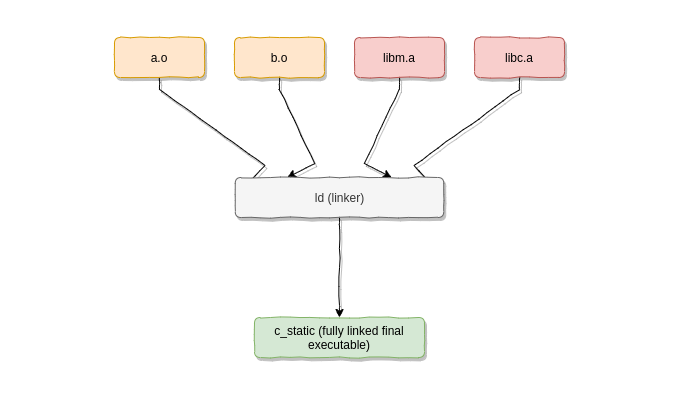

Static linking

Let’s create a final executable with the following command.

gcc a.o b.o -static -lm -lc -o c_static

(Or)

gcc a.o b.o /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.a /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.a -o c_static

In the above command a.o and b.o are linked with static libraries libc.a and libm.a.

Let’s check whether rand, printf and sqrt symbols are defined in the final executable.

$ nm c_static | grep -e "rand" -e "sqrt" -e "printf"

000000000001c090 T ___asprintf

000000000001c090 t __asprintf

000000000001c090 W asprintf

00000000000224d0 t buffered_vfprintf

000000000007e740 t buffered_vfprintf

000000000008c960 t _dl_debug_printf

000000000008ca10 t _dl_debug_printf_c

000000000008c320 t _dl_debug_vdprintf

000000000008cac0 t _dl_dprintf

00000000000c5760 D _dl_random

0000000000078520 T __fprintf

0000000000078520 t fprintf

00000000000231e0 t __fxprintf

0000000000023380 T __fxprintf_nocancel

000000000000cfc0 T __ieee754_sqrt

0000000000078520 W _IO_fprintf

000000000001bfc0 T _IO_printf

0000000000022f20 t locked_vfxprintf

000000000001bfc0 T __printf

000000000001bfc0 T printf

00000000000c9728 B __printf_arginfo_table

0000000000075f40 T ___printf_fp

0000000000075f40 t __printf_fp

0000000000076230 t __printf_fphex

000000000000c856 t __printf_fphex.cold

00000000000732c0 T __printf_fp_l

000000000000c851 t __printf_fp_l.cold

00000000000c9708 B __printf_function_table

00000000000c9710 B __printf_modifier_table

000000000001c6c0 t printf_positional

00000000000789d0 t printf_positional

00000000000c9730 B __printf_va_arg_table

000000000000cf42 T print_sqrt_random

000000000001b8a0 T rand

0000000000072100 t __random

0000000000072100 W random

00000000000af1c0 r random_poly_info

0000000000072570 t __random_r

0000000000072570 W random_r

00000000000c79a0 d randtbl

00000000000760f0 T __register_printf_function

00000000000760f0 W register_printf_function

00000000000780b0 T __register_printf_modifier

00000000000780b0 W register_printf_modifier

0000000000075fb0 T __register_printf_specifier

0000000000075fb0 W register_printf_specifier

0000000000078410 T __register_printf_type

0000000000078410 W register_printf_type

000000000000cf90 T __sqrt

000000000000cf90 W sqrt

000000000000cf90 W sqrtf32x

000000000000cf90 W sqrtf64

000000000000cfc0 T __sqrt_finite

0000000000071ec0 W srand

0000000000071ec0 T __srandom

0000000000071ec0 W srandom

00000000000721c0 t __srandom_r

00000000000721c0 W srandom_r

0000000000025d70 T __vasprintf

0000000000025d70 W vasprintf

0000000000025bd0 t __vasprintf_internal

000000000001f180 t __vfprintf_internal

000000000007b4f0 t __vfwprintf_internal

00000000000230e0 T __vfxprintf

As you can see here rand, __sqrt and __printf symbols are defined in .text section of c_static final executable.

In the case of static linking, the symbols are defined in the final executable before execution itself.

Let’s check the size of the c_static.

$ ls -lh c_static

-rwxr-xr-x 1 nayab nayab 875K Mar 11 19:48 c_static

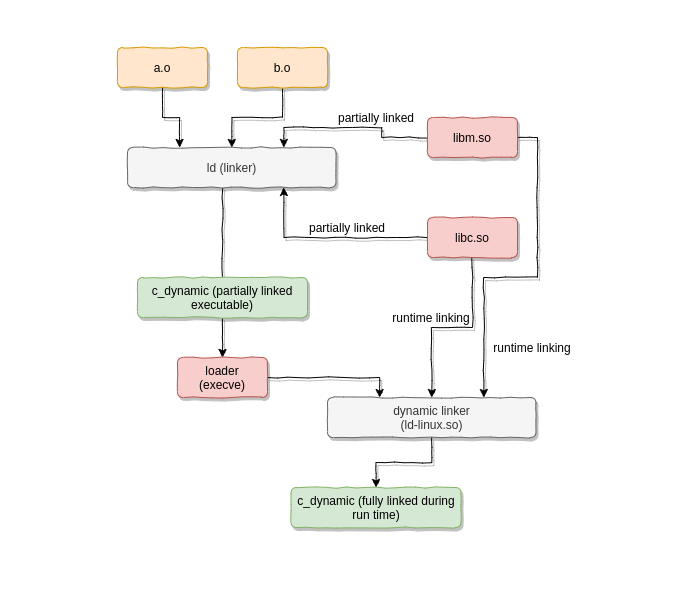

Dynamic linking

Let’s create the final executable by linking a.o, b.o with the dynamic libraries (also called shared object files).

gcc a.o b.o -lm -lc -o c_dynamic

(Or)

gcc a.o b.o /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so -o c_dynamic

Let’s check whether rand, printf and sqrt symbols are defined in the final executable.

$ nm c_dynamic | grep -e printf -e rand -e sqrt

U printf@@GLIBC_2.2.5

00000000000011a2 T print_sqrt_random

U rand@@GLIBC_2.2.5

U sqrt@@GLIBC_2.2.5

As you can see all the symbols are undefined (U). These symbols are linked during run time.

Let’s see the size of c_dynamic executable file.

$ ls -lh c_dynamic

-rwxr-xr-x 1 nayab nayab 17K Mar 11 20:01 c_dynamic

The size of the dynamically linked executable file much lesser than the statically linked executable. The reason for this is the symbols are not defined in the dynamically linked executable.

Behind the scenes of execution

What happens when you execute the binary c_static or c_dynamic in the shell?

To execute the binary, we run it in the shell prompt like following.

./c_dynamic

The shell reads the input and invokes the system call execve() to create a new process for this binary execution. Remember, shell is just an application program like any other.

The execve() is called loader and is responsible for allocating stack, heap and data segments in the memory for this process. It also copies .data, .text section from the executable into memory and transfers the control to the beginning of the program. That means all static or global/extern variables are initialized before the program execution itself.

We will use a command called ldd to see the dependent libraries of c_dynamic.

$ ldd c_dynamic

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffeeedbf000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x00007f0bcf22f000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f0bcf03e000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f0bcf3ae000)

The above information is placed in the c_dyamic by linker during the linking stage so that the loader knows which libraries have these functions defined in and which runtime linker to use.

The loader then loads the dependent shared libraries libm.so and libc.so into memory.

The library /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 in the above command is runtime linker and links the undefined symbols printf, sqrt and rand with the definitions present in shared libraries during run time - before the program execution.